Taking inspiration from the US Air Force in measuring price elasticity

You may already know this story…

During the Second World War, the American army was looking for a way to make its aircraft more resistant to enemy fire without making them heavier.

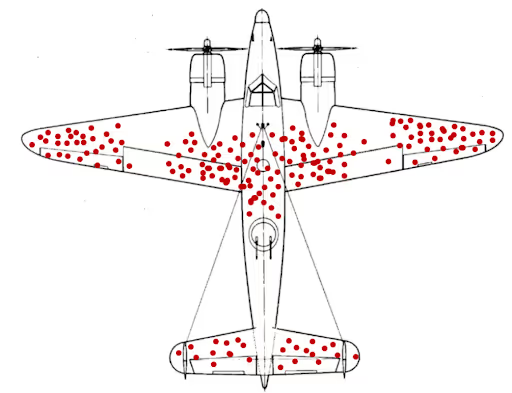

Analyses of aircraft returned from combat showed impacts concentrated on the wingtips, centre and tail of the aircraft. The Americans’ first conclusion was therefore to reinforce the aircraft where impacts had been observed.

But mathematician Abraham Wald disagreed. The bullets whose impacts were studied were not fatal to the planes, because the planes had returned. On the contrary, the return of the planes despite the bullet impacts proved that on the wings, centre and tail, the planes did not need to be further reinforced! His conclusion was that the vulnerability of the planes lay elsewhere… Sa conclusion était donc que la vulnérabilité des avions était à trouver ailleurs…

What does this have to do with price elasticity?

This story is generally used to present the survivor bias. It can be found in many fields: architecture, discrimination and….pricing! le pricing !

Pricing in the retail sector is a complex discipline. A balance has to be struck between competitiveness and margins, taking into account a multitude of constraints: the diversity of competitors in different catchment areas, product sensitivity, range consistency, and so on.

Price elasticity may therefore appear to be the antidote. The Holy Grail is to leave it to the elasticity coefficients to find the optimum price.

When it comes to physical retailing, we have our doubts.

Beware of survivor bias in your analyses

With elasticity analyses, we want to determine which price will optimise our sales volume/margins ratio. We therefore study the variation in demand for a good when we change the price. But in food retailing, purchases are recurrent and customer acquisition is extremely costly. Sales volume therefore corresponds to a customer’s purchases over the course of the year, not just during one visit to the shop.

To obtain an accurate measure of elasticity in a supermarket, we therefore need to be able to (1) measure the number of customers who saw the price, found it acceptable, took the product off the shelf and bought it. (2) Measure the number of customers who saw the price, didn’t find it acceptable, and won’t shop with you again. Whether they bought the product or not.

Put yourself in the shoes of a customer who has come to shop for the week. His basket is full, and he ends up with Nutella. On Nutella, he discovers an insulting price 30% higher than that of your competitor. I’m willing to bet that this customer will go to the checkout (with or without his Nutella) and say to himself ‘next time, I’m going to try out the competition because I feel like I’m being ripped off’. « la prochaine fois, je vais tester la concurrence parce que j’ai l’impression de me faire avoir ».

How will your elasticity coefficients take into account the experience of those customers who won’t be coming back? Will you be able to determine which of the 20,000 prices on the shelves will have driven your customer away? How can you take into account customers who fragment their purchases and visit other stores?

I’ve drawn 2 conclusions from this:

- Maths is very useful

- It’s dangerous to make the quality of your prices depend on the quality of your elasticity coefficients

Elasticity coefficients can be an additional aid in guiding pricing decisions, when the quality of prices is already guaranteed by compliance with pricing fundamentals. By ‘fundamentals’ I mean index management, vertical/horizontal chaining, sensitivity pricing and local pricing. But starting your pricing project by integrating elasticity coefficients is, as we say in German, ‘veschlimmbessern’ (doing better than worse).

And to get to the end of the story: Marc-André Désautels, another mathematician, pointed out that no data on the missing planes had been collected. He concludes that other problems, such as lack of fuel or mechanical damage, could be to blame for the loss of these aircraft.

So it’s vital to remain cautious in our own assumptions and conclusions: customers who didn’t buy your product when they were in your shop may have been disturbed by the music being too loud or the checkout queue being too long. And your elasticity coefficients will miss the point.

If you want to put in place the strategies that have proved so successful in physical distribution, let’s have a coffee together!